This is because landlords grappling with rents that don’t cover improvement costs often neglect maintenance, leading to a decline in housing quality. This neglect is not just a theoretical possibility, but a real-life consequence of rent controls. More importantly, rent controls discourage new construction by dampening investor enthusiasm since they fear future revenue limitations.

THE EVIDENCE LEAVES NO DOUBT – RENT CONTROL HURTS RENTAL SUPPLY

Yet a recent op-ed by Ricardo Tranjan, an economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, argued that rent controls “don’t reduce housing supply but they do limit profits.” The author cited several studies from Canada and the United States to argue that rent controls “stabilize rent increases without negative effects” and advocated for “bringing back rent control in units built after 2018” in Ontario.

We reviewed the studies cited by the author and found they all unequivocally demonstrated that rent controls contribute to a slowdown in rental supply, thus hurting the very people that rental advocates intend to help.

For example, Tranjan said a 2020 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. (CMHC) study sponsored by KPMG LLP found “no significant evidence that rental starts were lower in rent control markets than in no rent control markets.” But this is more of a case of being lost in translation than an actual finding.

The quoted text is from a four-page summary that CMHC produced from KPMG’s 90-page report. The detailed report’s findings are much more nuanced and do not endorse rent controls. A review of previous research led KPMG to conclude that “rent control has generally been found to have reduced rental supply due to the limits on rent prices.” This is a clear indication that rent controls are detrimental to rental supply.

Its comparison of rental housing starts in markets with and without rent control was rather inconclusive (“unclear”), which is hardly robust evidence to argue against the adverse impact of rent controls on new rental construction.

Tranjan also refers to a 1994 study sponsored by CMHC that found “no evidence that controls affect the responsiveness of apartment unit starts to either vacancy rates or rents.” This study falls short on two accounts.

First, the CMHC commissioned seven independent reviews of the study and they identified significant shortcomings. Second, a key finding was that rent controls did not impact the long-run rate of rent increases. This is quite the opposite of the argument that rent controls stabilize rent increases.

But what about recent research? Tranjan referred to a 2023 study published in the International Journal of Housing Policy (IJHP) that analyzed data from 16 countries to conclude rent controls do not reduce rental housing construction.

The op-ed also mentioned a 2023 letter by American economists to the Federal Housing Finance Agency that said “the Economics 101 model that predicts rent regulations will have negative effects on the housing sector is being proven wrong by empirical studies.”

One would assume the American economists must be sound urban empiricists for their argument to hold weight. Quite the contrary. Most signatories were respected experts and policy advocates, but not well-versed in urban economics. Fact-checking of the letter by the National Multifamily Housing Council in the U.S. revealed numerous distorted facts, suggesting the letter writers might not have understood the research they cited in supporting rent controls.

For example, the letter mentioned a 2019 study by three Stanford University professors on how rent controls helped lower tenant displacement in San Francisco. Here, the letter writers are guilty of not error, but omission. The study was more nuanced and concluded that “while rent control prevents displacement of incumbent renters in the short run, the lost rental housing supply likely drove up market rents in the long run, ultimately undermining the goals of the law.”

The preponderance of empirical evidence supports the argument that rent controls deter investors from investing in new supplies of purpose-built rental dwellings. Thus, the rental stock does not grow with the demand for rental dwellings over time. Such an imbalance between rental demand and supply results in ultra-low vacancy rates and rapidly rising rents.

Rent controls impose other distortionary consequences on labour markets. Those residing in rent-controlled units are less inclined to relocate even if better employment options are available elsewhere, thus restricting their long-term labour market outcomes.

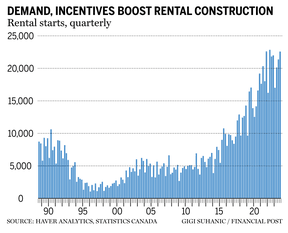

For a rebound in rental construction to match the numbers observed in the early ’70s, many administrative changes are needed, such as eliminating rent controls from market-based units. At the same time, the government needs to invest in non-market dwellings to assist those who have been priced out of the rental market.

The provision of affordable rental housing is a public sector responsibility. Shifting this burden onto the shoulders of private landlords is an example of the state shirking its responsibilities while hurting the long-term interests of renter households.

Story by: Financial Post